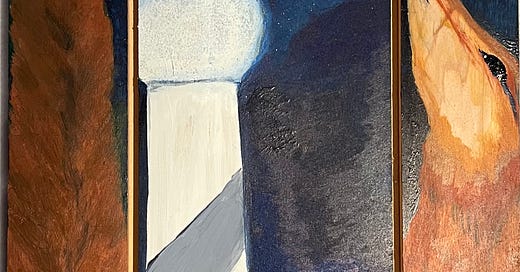

Reincarnation

As far as the medical profession is concerned, John is nearing the end of his life. As far as John is concerned, he has decades more to explore.

I have learned that when we are aware time is short, what is essential becomes magnified. The things that matter most rise to the top, while the usual "have tos" and "shoulds" of everyday life melt away.

It has been “a minute”1 since my last post. I know you know so that is redundant. It is for my own knowing to acknowledge that you may have felt or be feeling forgotten.2

You are not.

I will be sharing a separate post to illuminate what has risen to the top and therefore been keeping me from being HERE with you…soon3. Until then, I bring you back to the momentarily interrupted telling of the story of Reincarnation from Heart Sounds:

For most, asking a person what they would be doing if they weren't in the hospital is enough to illuminate the needs above the noise. For Mr. Randall, it would take a far more unusual question to amplify the notes that compose the true meaning of his life above the din of his fears.

****

“Do you think you are immortal?”

This is not a rhetorical question. It is not asked with incredulity. I really want to know the answer. I doubt many physicians have ever asked a patient that question, at least not out loud. I know I certainly never had, until now.

John Randall is sitting in an armchair in his hospital room as I kneel before him waiting for an answer. The glow of his yellow skin almost illuminates the room. And while his chiseled cheeks and chin suggest the elegance of the miniature wax busts of master composers that lined my piano when I was a child learning to play, John does not aspire to become the physical incarnation of his idols.

“Death is final,” he retorts, “why wouldn’t I want to do everything I can to be alive? I don’t want to become a fossil.”

As a concert pianist, he loves to listen. His ear is tuned to the subtlest intonations.

“You can listen to three different pianists play the same piece, and it is their interpretations which so fascinate me.” His eyes shine with the vibrancy of a five-year-old. “I love being alive. I love looking out the window at home and gazing at Mt. Tam while listening to the best classical music.” He then submits, “Did you know Comcast offers the best selection of classical music? Pandora becomes so narrow and only plays what it thinks you want. But to really listen and hear the differences, the nuances, the breadth … well, nothing beats Comcast.”

Just then one of our palliative care team members comments on the music from John's television tuned to the relaxation station, “And how do you like listening to this while you are in the hospital? Do you think it sounds pretty?”

“New age music is like eating cotton candy all day. It’s all pretty. Pretty in music is poorly defined. It has come to mean nothing but boring.” John segues this thought without pause, “Pain is a form of boredom because it’s so repetitive. Boredom is repetitive.”

Within moments of our meeting, it is clear that John is anything but boring. He is also not interested in becoming repetitive. He is consumed with experiencing everything, even the unimaginable. He loves the word possible and uses it when most would be much more comfortable replacing it with impossible. Such conversations have concerned and frustrated some of his medical providers, while they have awed and inspired others.

As far as the medical profession is concerned, John is nearing the end of his life. As far as John is concerned, he has decades more to explore.

In the world of medicine, John is considered terminally ill, with two different, rapidly advancing cancers. The one that has taken up residence in his liver is causing the yellow glow of John’s eyes and skin. The other has resulted in the removal of some of his tongue and esophagus, causing him to lose the ability to eat. Neither appears to diminish his seemingly euphoric existence.

In addition to enjoying the view of Mt. Tam, John eagerly shares his passion for watching the Food Network, “I find myself chewing on my tongue by the end of a program I am so intensely imagining the taste of the food. They make it all look so beautiful.”

You’d never know that John has been receiving all his nutrition via a tube that enters directly into his stomach. The irony that these canned foods even come in containers labeled vanilla, chocolate or strawberry never ceases to amaze me.

“I’d like to live another 10 or 20 years,” John offers spontaneously and matter-of-factly during our visit. “My father died when he was 83, and I’d at least like to live to see that age if not beyond. I think that’s reasonable.”

John is just shy of 70.

Despite his clarity of thought, it is evident that John’s experience of being alive does not match his body’s. While John continues to savor and seek more to learn and enjoy, his body continues to wither and decompose.

Said with a triumphant smile, John shares, “I just finished reading Don Quixote. So many people talk about the classics, the books we want to read, say we will read, but somehow never get to. Yet, I did! And I am ready for more.”

His hunger for life experiences seems unquenchable. And his perception of this fact is equally tantalizing. So is it any wonder that John considers his body’s progressive dysfunction as simply another experience that can be navigated because, “I’m not done living. I mean who is? To stop trying to prolong my life, to do everything and anything that can keep me alive…well that is like committing suicide and I would never do that.”

Knowing my colleagues are already feeling anxious about the future of John’s medical care, I feel compelled to press him further.

“Mr. Randall, is there any imaginable state you could be in that would be so undesirable that you would no longer want to live?” I ask this question looking up into his pondering eyes and watch as he receives the question the way I envision a great physicist contemplating a newly isolated atomic particle would.

“Well, I cannot imagine what I haven’t imagined, so I suppose not. I mean living is living. And dead is dead.” John pauses for a brief moment and looks to his right toward the window before returning his gaze to me, adding, “So long as my mind is thinking, this is all that matters in life. To think and to imagine.”

Knowing what I can imagine in the reality of medicine, I push on for even more clarity. “Would life be acceptable to you if you were unable to leave the hospital and return home to your view of Mt. Tam? Where your body would be confined to lying flat in bed and you would be connected to machines that, while keeping your lungs and heart functioning, would prevent you from communicating. You would most likely be in a coma.”

John doesn’t hesitate before answering, “I would be looking out my window and viewing Mt. Tam. It would be like a movie. And really, what is the difference? As long as I am alive, I am thinking. That is really what is essential.”

“For how long?” I hate that I asked this question the minute it escaped my lips because I know it is impossible to answer. Yet, I am committed to supporting his goals to the best of our ability, and the best way to do that is to be as clear as possible.

“Well, I will know at the time it is happening and let you know.”

This is precisely the answer everyone helping to care for John fears. This answer, and the perspective that this answer is possible, is far from unique to John. And that is the crossroads where medical providers loathe to meet the patients and families we have the privilege of caring for.

The breadth of John’s seamless and clear imagination is staggering.

“What would it take to replace the function of my liver? Can you just attach me to a machine and clean out the things the liver does, the same as you do for kidneys?” he asks.

“What a wonderful idea," my colleague replies. “I wish we could do that right now. And perhaps someday we will be able to do that for other people.” Her answer, spoken with sincere reverence and grace, does not quench John’s curiosity.

“Well, what about a new liver? I do believe you can transplant livers. Am I correct?” His question is posed in a manner akin to a rabbi engaging in thoughtful discussion of a congregant’s interpretation of a passage in the week’s Torah portion.

“Liver transplantation is done, you are correct,” I say. “And I will be plain with you as you are being with me. You cannot have one.”

“Well, why not?” Asked so simply, you would have thought John is requesting a substitution on a dinner menu.

“Livers used for transplantation are limited. Most come from people who have died suddenly. And the number of people who need one far exceeds the number available. So, we have to do our best to make sure that the person who receives a liver will be able to use it. In other words, they have to be healthy enough to tolerate the procedure while sick enough to need one.” I wait for some sign of acknowledgement before adding, “Someone in your condition with metastatic cancer is not eligible.”

“Oh, I see. Thank you for being so clear.” John does not seem disheartened in any way with this conversation. He really seems to be present to the experience as a new experience, a living experience.

And so, this is when I ask, “Mr. Randall, do you think you are immortal?”

“Can you say that again?” His hand is cupped to his left ear in keeping with the grandfatherly demeanor of his body.

“Do you think of yourself as immortal?” I repeat with genuine curiosity.

Looking toward the window, he takes a deep breath. When he turns back, he looks more deeply into my eyes than he has before, leans closer and says, “I don’t know.”

I can finally appreciate the blue that the bile building up in his eyes is attempting to obliterate. I feel as if I am holding my breath waiting to hear what he will say next.

“The universe will at some point become a single point of atoms at which point everything will have died. So even the universe is not immortal.” He sits back in his chair and cogitates out loud, “And who really wants to live 30 million years? I’m not saying that. And yet, who’s to say what mortality is? What is the end? In a coma, how do we know what a mind is capable of imagining? I could be connected to a machine that someone has yet to invent, and suddenly you’d be able to hear my thoughts.” He speaks this with all sincerity. I cannot call it magical or even wishful thinking. He isn’t speaking in terms of miracles the way others I have cared for cling to when facing the unimaginable. He is not looking toward supernatural powers to see him through. He believes in the ingenuity of the human brain. He hopes, deeply, in the imagination.

“Hope is irrational, by definition,” he chuckles. “When I listen to a music recording, is my thinking of these musicians their reincarnation?” John ruminates for a moment longer before adding, “Maybe Jesus is reincarnated every moment people think of him, even if in vague ways.”

“When people think about you, what do you wish they would know?" I ask.

“That I love them." A tear forms in the corner of his eye which he does not attempt to brush away as he speaks, "And even if I go tomorrow, I’ll still be with them.” He quietly adds, more to himself than to me, “I hope I don’t ... maybe there is nothing on the other side.”

At the conclusion of our visit, I am certain John will end his life on his terms, which, in medical terms will mean being transferred to the intensive care unit where he will subsequently be attached to life-support machines to keep his heart beating and his lungs breathing. And while his clearest wishes are to keep his mind thinking, no such machine yet exists to guarantee we can.

****

I was wrong.

Forty-eight hours later, after reading a draft of this story, John left the hospital. He unexpectedly chose to engage with hospice care at home. He asked that I visit him. That I publish this story with his name. He also asked to avoid any resuscitative medical care. In other words, he wished to allow a natural death.

He died a week later, before I got to see him again.

I think of him whenever I hear certain pieces of music: classical piano on my car radio causing me to ponder the merits of Comcast; the song, There's So much Energy In Us, by the band, Cloud Cult, which I set to play on repeat as I wrote this story while taking a cross-country red-eye after my one and only meeting with him; and the ever present "pretty" melodies emanating from relaxation channels in the hospital rooms of so many patients, forever conjuring cotton candy. John’s infinite energy now transcends space and time. And I can’t help but wonder, does he feel this reincarnation in my mind?

A turn of phrase my 23 year old (and on occasion, his not-that-either-will-admit-it-idolizing 16 year old sibling) says as a way to acknowledge more time has passed than intended before attending to X (or Y or any other letter or symbol you prefer to denote what blank you wish you had filled).

My next book, (foreSHADOWING) shines light on that feeling…. :)