Wings to Fly

When pain is quelled, people can come back to life. Not cured, rather back to how they know themselves to be.

“I am so lucky.”

These are not the words I expected to hear from the teenage-like 38-year-old man suffering the excruciating pain of incurable colon cancer. But Brian is anything but expected.

Brian White is, in fact, white, but more so now due to lack of sunshine having the opportunity to kiss his face and body. He is too tall for his bed, reaching upwards of 6’3” and I, all too often, bump his size 16 feet dangling over the sides of the bed as I walk around to greet him. His constant companions, Mooch (the sure-footed American short-haired gray cat) and Dexter (the unflappably loyal, though less-than-dexterous, beagle), and their ability to discover space in this overcrowded bed, border on miraculous.

Brian was raised solely by his mother, Gale, after his father helped him discover the power of drugs as a young teen when innocence still trumped common sense. Brian’s tolerance to medications is like nothing I have ever encountered. His pain is likewise off the charts. And his capacity to express gratitude ultimately transcends all.

I quickly learn his most recent hospital admission provided him with endless pokes and prods, tests and procedures, resulting in profound weight loss, fatigue and frustration. Most notably, Brian has significant pain, the physical source of which is obvious when one examines his abdomen. But the impact of that mass, clearly reaching beyond the direct nerve endings it presses against, is now infiltrating Brian’s heart and soul, making pain management anything but straightforward.

In hospice and palliative medicine, pain is the first symptom we ask about and assess for, even when people are not able to answer. We do this because we know pain, whether physical, spiritual or emotional, overrides all other sensations. Until pain is controlled, we are unable to address any other concerns or wishes. When pain is quelled, people can come back to life. Not cured, rather back to how they know themselves to be. This is when palliative and hospice care really take flight.

Within days of Brian’s return home, his pain medication requirements demand aggressive intervention, such that a continuous infusion of opioids is needed, and even this only takes the edge off his pain. Eventually, his pain medications are escalated to the maximum capacity of the largest delivery pump the infusion company can provide. Adjunctive IV medications are soon added to potentiate the effect, finally providing enough relief so Brian can re-engage with life. I finally get to see him smile and hear him joke.

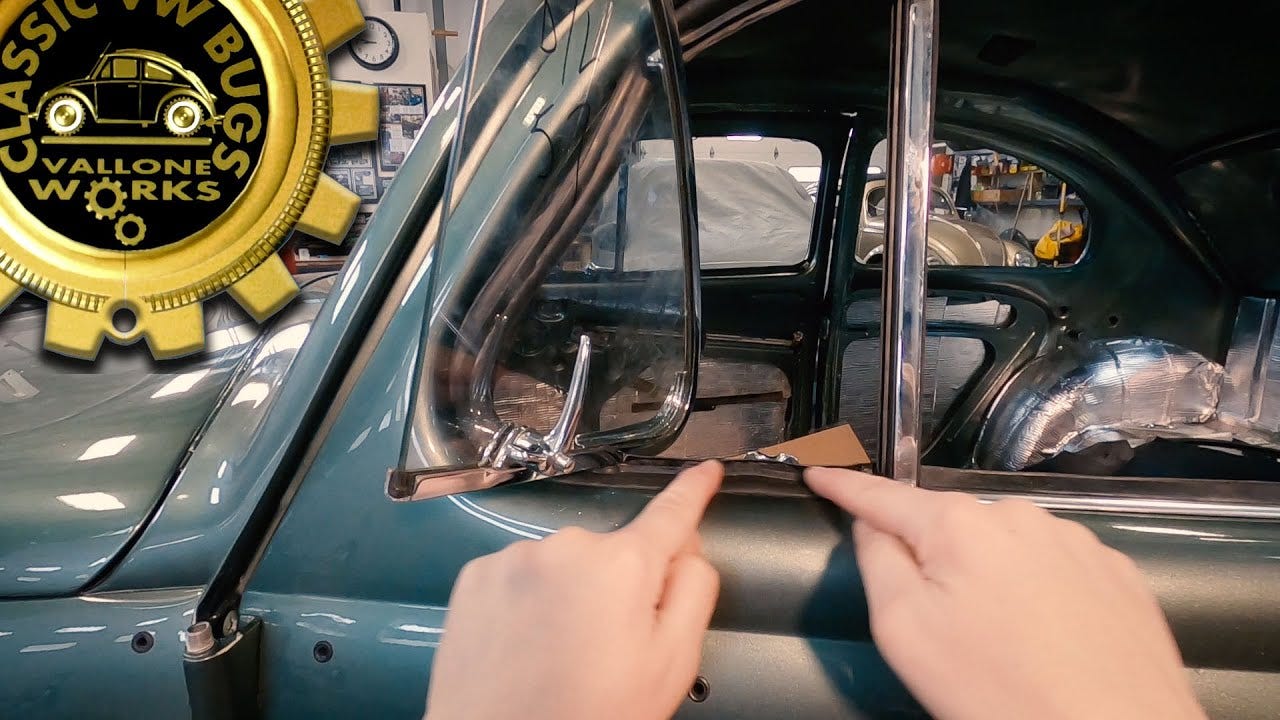

This glimmer of joy reminds Gale of how her son used to be before he developed cancer. "At the age of four," she shares, "I owned a sky-blue VW bug." Gale laughs as she remembers, "Every time we'd pile in, Brian would say, 'Open the windows,' pointing to the push-out triangular windows on the front doors of the car, 'so I can fly!'" Gale laughs some more, then sighs. "I never stop wanting to hold him. He's still in there, that happy kid, even now."1

With his improved pain management, Brian begins to ask for simple things: food, friends and “…maybe even a little sex. I may be tired but I’m still horny.” With that last statement, I can’t help but notice Brian’s gaze focused on the opening in my blouse as I finish leaning over him to examine his abdomen. Somehow, his words don’t seem crass or embarrassing. They seem human. And Brian’s mom seizes the opportunity to start nurturing her son’s starving constitution.

“Perhaps we can have one of your girlfriends come over in a few days if you’re feeling up to it.”

Brian begins to eat everything in sight. I know this is mostly due to the steroids I have started him on and that it will be short-lived. So, Brian and his mom live it up. Breakfast burritos, Whoppers, Little Lucca roast beef sandwiches, sloshed down with Giant Gulps of Coca Cola. Popcorn and pizza at any hour of the day are fair game. Though the TV is on nearly 24/7, I can’t say Brian ever actually seems to be watching.

“Maybe it just keeps him feeling normal,” Gale muses when I ask.

During this honeymoon period, the period of pain relief before complete bowel obstruction, I get to see the love Brian has for his mother. How after each request he makes of her or even every few minutes when no request is made, he sings out “I love you mom” and her immediate rhythmic reply, “I love ya Brian.” Like a heart beating in unison. And even though they each know it won’t last, asking me in private nearly every visit, “How much more time?” neither lets it get in the way of being present in the moment at hand.

Just shy of three months at home, football-teams-worth-of-food devoured, hours of television absorbed (or not), everything begins to stop working as the cancer continues to grow. Brian develops relentless nausea and vomiting from the bowel obstruction, and as a result, his pain becomes intractable. No medication will halt this now, and Brian refuses to return to the hospital for any more invasive procedures. Not surprisingly, Brian becomes very fatigued and very angry, yelling at Gale and even kicking Dexter off the bed. (Mooch seems to sense the changed environment and chooses to stay clear by perching atop the recliner in the living room instead of on Brian's bed.)

Brian refuses my visits altogether.

Gale explains when I call, “He says nothing is helping, so what’s the point?”

Brain's resignation feeds into my own sense of helplessness. I wrack my brain (as well as many of my colleagues: medical, social and spiritual) for some insight. But Brian continues to refuse to see anyone except for one favorite nurse. And therein lays the magic.

Brian does want to be with people, and people want to be with Brian. And in the end, focusing on what makes Brian happy, even in the face of chronic pain and suffering, is what saves him, as well as the rest of us.

Brian’s birthday is fast approaching, as are his final days. I have learned that waiting for such milestones to arrive may result in missed opportunities instead of joyful celebrations. With this in mind, I seize the first model of a VW bug I can lay my hands and leave it on the doorstep, respecting Brian’s wish not to see me.

Gale phones me later and says Brian appreciated the car and welcomes my visits again.

I don’t even bother asking him about his pain, I simply sit with him and hold his hand. And that is when he says, “Thank you, Dawn. Thank you for caring. I am so lucky.”

Brian knows I am not able to take his pain away. Suddenly, it doesn’t matter. Being alive and not being alone is all that he wants now.

When the clock strikes midnight on Brian’s 39thth birthday, with decorations covering the walls of his room, Gale sings Happy Birthday and Brian smiles, knowing the day has arrived. His voice, now raspy due to extreme fatigue, still whispers, “I love you mom.” Gale’s ever-ready “I love ya Brian” follows in reply.

In the morning his two favorite nurses and uncle join his mom and sing again showing him all the presents and cake they have brought him. Everyone knows he will never use them or even take a bite. But that isn’t the point.

As the morning wears on, Brian develops a change in his level of consciousness, signs that his death is approaching. I press into Brian’s giant, now skeletal hand a tiny custom-painted sky-blue beetle with triangle windows I have fashioned so they can point out the front doors.

Brian slowly turns his head my way, opens his eyes and mouths some words, while his mother’s cupped hand covers her own as she closes her eyes in disbelief.

Over his final days, Brian continues to have intermittent signs of pain for which we continue to provide aggressive interventions, including medications that I anticipated would have fully sedated five men, but not so for Brian.

Perhaps Brian’s body has developed physiologic tolerances to medication due to his history of substance use disorder. But I also wonder if his body, now no longer numb, actively fights to maintain sensations: joy, love, nausea and pain, all of which provide equal evidence that he is still alive.

Brian intermittently regains consciousness, and when he does, it is always to utter his love and thanks, with Gale’s harmony echoing in return.

Shortly after his death, I phone Gale to see how she is doing and to say how much I miss them both. She shares how she has decided to bury Brian with the sky-blue beetle and thanks me for all my care and kindness. But this time, she concludes with the same pitch and rhythm, “I love ya Dawn” as she hangs up the phone.

A version of this story originally appeared in San Francisco Medicine.